Creating the Dream Team

Byline: Megan Steller

There are some practical steps that go into creating a new chamber ensemble: you must find exceptional performers, choose a program that both exhilarates and moves, book in rehearsal times and let the work begin. And then there’s an ingredient that’s not so easy to put a label on, a certain magic that is impossible to describe. It’s the spark that you see when three people come together from disparate practices and make the art come completely alive in front of your eyes. As a listener, you might have experienced it before; the shiver that goes up your spine when new collaborators look at one another and begin, completely together, as if they’ve played alongside one another for a lifetime. It’s rare, and there’s nothing quite like it.

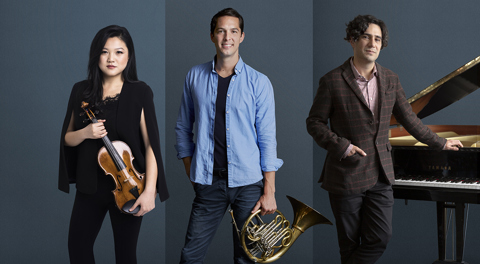

I asked the acclaimed pianist Amir Farid about whether there is something unexplainable about the feeling from a performer’s point of view, and he agreed that there was: ‘There are so many immeasurable variables as to why a group of musicians get together and play very well, and others get together and play immaculately. And it’s not just in chamber music that this is the case – it’s in every piece of art that you create. It’s the soloist’s relationship with the composer, or the orchestral player’s relationship with the person sitting next to them; it can take a long time to know a composer’s mind and heart, but when it’s there, it’s there.’ It’s something that none of the three musicians you’ll see on stage tonight worries about, though. I noticed as we each spoke that each member of the trio has a special kind of trust – in each other, in the music, in the magic. The three may not have spent much time together, but there’s something incredibly special about their approach to collaborating. Each echoed the feeling of knowing that they would all show up fully, with flexibility and with open hearts to the music and to one another.

Preparation is a solitary art in many ways; before the collaboration, you must spend hours alone with the notes. There is time getting to know the composer, the intention, your own changing feelings about the repertoire. I was curious about whether recent changes to restrictions, and the somewhat forced solitude would impact our musicians’ preparation, considering rehearsal timelines are perhaps shorter than they usually are, but none seem fazed. Violinist Emily Sun and horn player Nicolas Fleury have both lived and worked for stretches in the United Kingdom, and are used to a fast-paced working environment, where timelines ahead of a performance can leave something to be desired. And for Amir, who splits his time between New York and Australia, it’s less about time in the room, and more about how you show up. This was an oft-repeated feeling as I investigated the ‘new normal’ of chamber music preparation: ‘you have to be flexible,’ Nicolas told me, ‘flexible in your preparation, so you can arrive and fit with your ensemble, and flexible as you perform. We get this beautiful opportunity to play these incredible works many times, and as you travel and perform in new venues, things change, and the more relaxed you are, the better.’